Can Female Viagra Addyi - or Any Medication - Boost Female Sex Drive?

_600x.jpg)

Flibanserin, the active ingredient in Addyi, has failed to make much of a dent in the problem of hypoactive sexual desire disorder, the most common form of female sexual desire disorder.

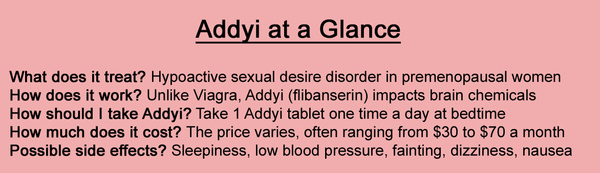

It has now been a little more than a year since Addyi -- the so-called female Viagra -- went on sale in the United States.

Its performance in that period has been lackluster, failing to live up to the hype claimed by its proponents in the long and tortuous fight to win the Food and Drug Administration's approval for the drug.

All of which begs the question: Does Addyi or any other drug have the potential to fire up the libido in women who have lost their desire for sex?

Although the FDA approved Addyi In August 2015, it attached a number of stringent conditions to its approval, not the least of which was a black box warning of potentially serious side effects -- severe hypotension and possible loss of consciousness.

No Drug for Females?

One of the primary arguments of the pro-Addyi faction was the absence of any prescription medication for the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women, of which low sexual desire was the most common manifestation and a condition that Addyi purportedly could treat.

Even the Score and other organizations actively supporting the pro-Addyi movement argued that this seemed somehow sexist given the many options available to men for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, one of the most common types of male sexual dysfunction.

Flibanserin -- the active ingredient in Addyi -- had been in FDA's drug approval pipeline for a lengthy period. Boehringer-Ingelheim, a major German pharmaceutical company, was the first to develop flibanserin. The firm tested it as a possible treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder, or HSDD. Among women, HSDD is the most common form of sexual dysfunction.

Boehringer Petition Rejected

On June 18, 2010, the FDA rejected Boehringer's petition for the approval of flibanserin, stating that the adverse side effects outweighed any discernible benefits of the drug. After mulling this rejection for a while, Boehringer made it known that it was abandoning the project and offering its patent on flibanserin to the highest bidder.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, a small, North Carolina-based company created primarily to get a female drug approved, in early 2011, bought the patent for flibanserin and began conducting research of its own to test the drug's efficacy in treating HSDD.

In June 2013, Sprout submitted a revised petition for flibanserin to the FDA, which later that year rejected the bid, again stating that there were adverse issues. Side effects, including dizziness, fainting, fatigue, nausea, and sleepiness, outweighed flibanserin's modest benefits.

(2)_600x.jpg)

Although the FDA eventually approved flibanserin, it attached several conditions to that approval, including a requirement that the packaging materials carry a black box warning of potential side effects.

Sprout Presses On

Sprout refused to give up. In December 2013, it appealed the FDA decision and filed a formal dispute resolution with the drug regulatory agency.

In response to Sprout's action, the FDA offered specific suggestions about additional testing that might convince the agency to give flibanserin the go-ahead. Sprout took the agency's advice and conducted extensive additional clinical testing to resolve some of the FDA's concerns about the drug and its side effects.

As Sprout's single-minded determination to win FDA approval for flibanserin played out, women's organizations -- some of the recent vintage and others long-established -- began lining up on opposite sides of the issue.

Among those crusading for flibanserin approval were Even the Score and Women Deserve, both of recent vintage. Opposed to flibanserin, primarily because of its multiple adverse side effects, were the American Medical Women's Association, National Women's Health Network, and Our Bodies Ourselves.

Sprout Resubmits Petition

On February 15, 2015, Sprout resubmitted its petition for flibanserin, including data on extensive additional testing it had conducted as suggested by the FDA.

In early June 2015, an FDA advisory panel voted 18-6 to recommend that the FDA approve flibanserin, which the agency did a little more than two months later, on August 18, 2015. Flibanserin officially became available by prescription on October 17, 2015.

As previously noted, after all the hue and cry about the desperate need for such a drug, on the one hand, and the dangers such medicine might cause, on the other, consumers seem less than eager to give the new medication a try.

Addyi Demand 'Underwhelming'

According to the National Women's Health Network, admittedly an opponent of flibanserin from the start, demand has been "underwhelming, perhaps due to its high risk and low benefit." NWHN reported that at Addyi's sales peak in March 2016, with over 1,500 prescriptions distributed.

This compares most unfavorably with the 500,000 prescriptions written for Viagra during its first month on the market. NWHN further reported that by May 2016, the monthly number of Addyi prescriptions had fallen to roughly 1,000, indicating a significant drop-off in interest in the drug.

For years now, long before the FDA's conditional approval of Addyi, proposed drugs to treat female sexual dysfunction have been referred to both collectively and individually as "female Viagra" or "pink Viagra." At least in the case of Addyi, such a label is grossly misleading.

While Viagra and the other oral ED drugs that have followed in its wake work by temporarily optimizing blood flow to the penis, thus facilitating the erectile process, Addyi seeks to fire up the female libido by rebalancing the brain chemistry.

Some medical professionals believe that abnormally low levels of testosterone can cause a loss of sexual desire in women.

Comparable to an Antidepressant

In that respect, Addyi is more akin to an antidepressant than a male drug for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Addyi seeks to increase sexual desire by suppressing the brain activity of serotonin. A neurotransmitter believed to inhibit sexual desire and function while increasing brain levels of dopamine and norepinephrine, which promote sexual desire.

The absence of any drug for treating female sexual dysfunction fueled the push for Addyi's approval despite clinical trials that showed only a minimal increase in libido among those tested.

In its one-year report card on Addyi, NWHN points out that nine out of every ten women test experienced no improvement in sexual desire. And that paltry showing was achieved when Sprout insisted on using a new yardstick to assess flibanserin's effects on sexual desire.

Study Finds Low Level of Efficacy

Casting yet another cloud over Addyi's prospects was a Dutch-Belgian study published in the April 2016 issue of "JAMA Internal Medicine." The research team evaluated data from five published and three unpublished studies covering nearly 6,000 women.

Researchers found that treatment with flibanserin resulted in only one-half of an additional satisfying sexual event per month. While statistically and clinically significantly increasing the risk of dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, and fatigue.

Women reviewing the studies can conclude that the benefit, such as it is, is far outweighed by the possible side effects.

To be fair, Addyi's lackluster sales performance in its first year on the market may very well be reflective of factors other than the drug's efficacy. The black box warning mandated by the FDA could well be scaring away potential users, as could the potential dangers caused by concurrent use of Addyi and alcohol.

To safely use Addyi, potential users must swear off all alcohol use for as long as they take the drug. It appears that some women are unwilling to make this sacrifice, mainly when the drug's success rate has been so modest.

Price Too High for Some Women

NWHN estimates that Addyi, taken daily to be effective, carries a price tag ranging from $800 to $1,000 per month.

It said that as of August 2016, Drugs.com listed a 30-day supply of Addyi at $856. Because of its high cost, potentially serious side effects, and underwhelming performance, many insurers have been hesitant to cover the drug, according to NWHN.

Those who crusaded valiantly for flibanserin consistently pointed to the sexist implications of multiple drugs for male ED and not a single treatment for women (at least until flibanserin was approved).

However, this fact points to the essential differences between sexual desire and function in men and women.

While the preponderance of men's ED problems stems from insufficient blood flow to the penis, a physiological problem. Female sexual desire would at least superficially appear to be a psychological problem. ED in some men is psychological in origin, and that form of impotence is far more challenging to treat than the more common ED caused by compromised blood flow.

Among women an abnormally low libido is the most common form of sexual dysfunction.

Could Testosterone Help?

Even as Addyi's first-year performance casts serious doubts on its long-term viability, medical science is looking for other ways to help women fire up sexual desire. Several have suggested that testosterone supplementation might serve as one way to achieve that goal.

As most readers know, testosterone is the primary male sex hormone. However, it is also present in females, albeit at considerably lower levels. Women usually have about 10 percent of the male sex hormone, as is routinely found in men. And in both men and women, testosterone plays a key role in maintaining healthy levels of sexual desire. Although hormonal problems could result in lower than normal testosterone levels in women of any age, hormone deficiencies are most common in menopausal women, whose production of all sex hormones has decreased.

British Gynecologist Backs T-Supplements

British consultant gynecologist Nick Panay, M.D., a past president of the British Menopause Society, recently told the Daily Mail, "I strongly believe testosterone should be made available to all women who would benefit. It's not just about a lack of sex drive." Dr. Panay said that some of his female patients who've received such supplements had reported significant improvements in energy, mood, muscle strength, stamina, and well-being.

The continuing absence from the market of a broadly effective medication for the treatment of abnormally low sexual desire in women has not been lost on the FDA, which in October 2016 issued new guidelines for developing such medications.